Africa’s entrepreneurial culture is vibrant. According to the African Economic Outlook 2017 report, about 80 percent of Africans view entrepreneurship as a good career opportunity. The continent has the highest share in the world of adults starting or running new businesses. However, these entrepreneurs face a wide range of challenges and around 20 percent of SMEs across Africa consider access to finance the most important.

The impact of a thriving SME sector on an economy – particularly one with as much potential as Africa’s – is well-known: job creation, improvement and development of skills and knowledge, innovation, infrastructure development, and substantial economic growth. In Africa’s case, the successful growth of SMEs and entrepreneurs would lead to the much-anticipated industrialisation of many of the continent’s countries and sectors.

However, the African Economic Outlook 2017 report found that SMEs are financed only 20 percent of working capital by banks in Africa and according to the International Finance Corporation (IFC), “up to 84 percent of SMEs in Africa are either unserved or underserved” in terms of access to capital.

It is concerning, especially considering that entrepreneurs starting a new business need seed capital. Given that these young firms are often risky, PE finance can meet their needs. Research by the African Economic Outlook 2017 report shows that, in OECD countries, young firms often face a credit crunch 12 to 24 months after their creation. By then, the entrepreneurs have exhausted their personal resources, and their firms may be too small to qualify for formal banking loans.

The Power of Private Equity

In 2015, The Economist warned that “too much money is pouring into too few funds, chasing the few big deals on offer”. It is noteworthy, though, that African PE is still emerging as an institutional asset class.

In the 1990s, there were approximately a dozen Africa-focused PE firms, collectively managing around $1bn. This number has since spiked to over 200 firms, managing more than $30bn. Between 2010 and the first half of 2016, there were 928 reported deals, with a value of $22.7bn. Firms raised $17.3bn from 2010 to the first half of 2016 and invested in every region of the African continent.

Of the new money raised in 2016, nearly 70 percent was accounted for by three of the largest funds: 1. the Abraaj Group, who has deployed $3 billion across a range of sectors including healthcare, financial services, logistics, consumer goods, and food and beverages; 2. Helios Investment Partners, a $3 billion Africa-focused PE firm that manages a family of funds and their related co-investment entities and operates in 35 African countries across a range of industry sectors; 3. Blackstone Group, one of the largest PE funds in the world who has invested nearly $2 billion in African infrastructure projects, through its subsidiary Black Rhino, in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Nigeria and Togo.

Given their size, they need to make large cap investments to put the capital to work, but the pool of potential targets is limited. There are only 400 companies in Africa with annual revenues greater than $1bn, whilst consultancy firm McKinsey estimated that there are over 10,000 African companies with revenues of $10m to $100m.

More Than Money

Many of these SMEs could be well served by PE and the ability and discipline it can bring, including technology-transfer, managerial capability and financial acumen.

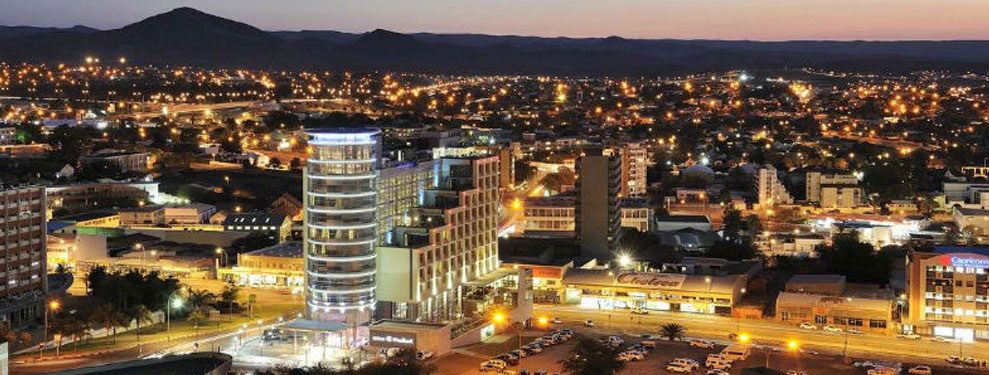

Jerome Kisting, Managing Director and Portfolio Manager of Namibian based venture capital fund Baobab Capital, explained, “Whilst we inject capital into SMEs, we are also involved in managing the businesses. We believe the monetary investment is not enough on its own. People need access to a level of financial management expertise, networks, and other markets. With every investment we make we try to understand how we can add value as well.”

This approach is especially important, given that they are operating in previously under-developed high-growth sectors that have yet to reach scale, such as education, healthcare and other consumer-facing industries. Yet, despite the vast number of SMEs operating in African countries, the overall market for risk and growth capital available to these types of businesses stay small and fragmented.

A persistent “equity-financing gap” is prevalent in an environment where sourcing any external capital, even debt, is challenging for these companies. Overall figures for the equity gap are difficult to determine; the World Economic Forum has identified a persistent gap in financing for businesses that need between $50,000 and $2 million in external capital.

Furthermore, due to changes in commodities prices and shifts in African nations’ national economic policies, the import and extractive industries that have dominated African economies for decades are giving way, allowing for consumer-facing and service orientated firms to enter critical growth phases that could lead to economic transformation. These companies need capital in the form of PE, ideally venture capital financing, tailored to their needs.

A new wave of “missing middle” funds will, therefore, create a dynamic pipeline of future investments for the bigger, traditional players in African PE. At the same time, growing smaller African companies into larger companies is not only good for PE firms at all points in the financial value chain, it is also good for overall economic development. The result will be a growth-focused PE in Africa with a vital impact on job creation and economic development.

Mr David Nuyoma, former Chief Executive Officer of the Development Bank of Namibia, now running the Namibian Government Institutions Pension Fund (GIPF), explained, “Venture capital is the biggest opportunity and challenge we face in the SADC region to ensure SME growth and Entrepreneur growth with much-needed mentorship and risk.”

A study by the African Venture Capital Association (AVCA) examined 199 African companies backed by PE between 2009 and 2016. These companies generated a net increase of 10,990 jobs, a growth of 15 percent and financial firms taking part in the study created 6,399 jobs. The AVCA study also found that PE firms in Africa educate investees and transfer actionable skills, implementing job-quality initiatives and strengthening competencies in human resources, corporate governance and general management expertise.

More and better quality jobs translate into aggregate positive effects on, among other things, health and education. Both are contributors to stability, which is conducive to creating an attractive business environment for new companies, the development of which will, in turn, make it easier to find new growth-oriented targets for middle-market funds, starting the virtuous cycle again. Jerome Kisting commented that “When you are in a developing country, it is difficult to remove the development impact of capital. It is going to have a socioeconomic impact.”

Given the dire need to create jobs for millions of young people in Sub-Saharan Africa and the positive outlook for SMEs in the middle-market PE space, Africa should be of greater focus for investors and venture capitalists of all sizes and specialisms.

Whilst African countries account for only 3 percent of global GDP, they make up less than 0.1 percent of institutional investor portfolios. The expansion of investment allocations for first-time funds and emerging managers, alongside the creation of funds that can help bridge institutional investors’ constraints and the small size of middle-market funds, would go a long way to support the next wave of PE investment across African markets. Thus, the more PE.